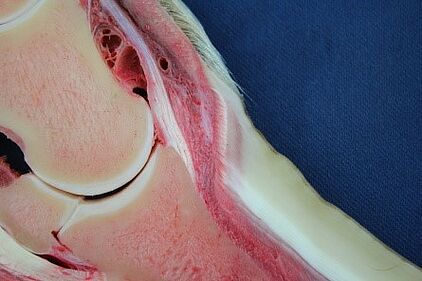

Normal hoof without laminitis

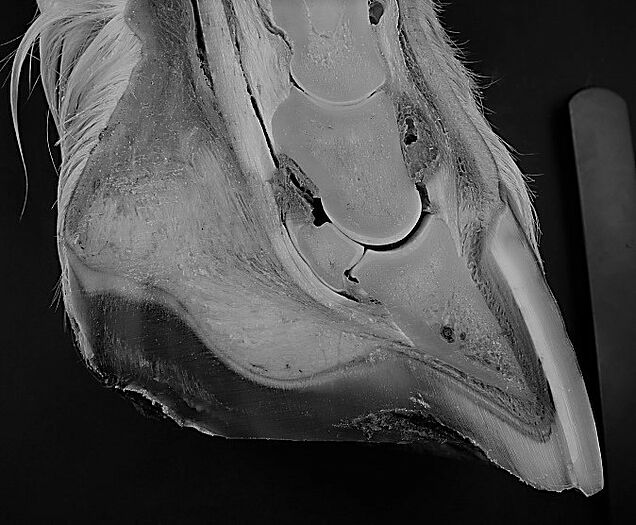

Chronic laminitis, Mary the pony

Chronic laminitis is diagnosed with coffin bone rotation when the toe wall no longer runs parallel to the front of the coffin bone. An attempt is made to prevent this coffin bone rotation in acute founder, always focusing on the diseased lamellar corium and associated separation.

Further changes to the coronet and sole are less well-known yet inevitable sequelae in laminitis.

Not every laminitis case is the same. The suspensory apparatus widens depending on the factors triggering laminitis and individual hoof position. Rare cases have seen the hoof wall still run parallel to the coffin bone and the hoof sink without rotation, albeit only in the initial stages. The front part of the hoof wall will deform depending on hoof angle, height and tendon and ligament tension; however, this deformation affects not only the toe wall at the front, but also the side walls.

Changes to the coronet may also vary; a sunk coffin bone pushes the papillae on the coronary corium into a horizontal position.

There are even changes to the frog and bulb.

Coffin bone rotation leads to a more oblique orientation in the coronary corium depending on the type of rotation (more on that later in the text). Even so, there might not be any changes of its original form and alignment in cases of simple coffin bone rotation at the coffin joint.

The sole edges always show the same changes, albeit only at first glance. Closer inspection will reveal major differences: The edge of the coffin bone will compress the reticular dermis at the corium in the toe area depending on the cause of the laminitis and how the individual position of the hoof has been compromised. Changes in the sole corium always affect the edge of the coffin bone. Visible changes to the coffin bone edge on the X-ray are always a strong indication for changes to the sole corium, which must be taken into consideration.

Collectively generalising all of these possible and variable changes in the corona, wall and sole as laminitis does not do justice to the problem. By the same token, there is as little justification to taking the same kind of treatment approach. We need to adjust our approach to prevent laminitis and adapt treatment to varying conditions to restore the patient’s hoof to its proper function.

1. Coffin bone rotation

Differentiating between forms of coffin bone rotation would help reach a more accurate diagnosis and treatment approach in laminitis. There are three possibilities here:

1. Coffin joint flexion: The coffin bone is indeed rotated at the coffin joint, that means, the coffin bone is flexed and positioned more steeply. The navicular bone is pushed up and out of the joint surface. There are also distinctions in rotation:

a) The rotation is actually due to a steeper coffin bone position.

b) The coronet flattens out due to sunk fetlock while under load.

2. Hoof wall rotation: The horn capsule is rotated around the coffin bone, and the front coronary horn is no longer parallel to the coffin bone.

3. Coffin bone rotation: A combination between 1 and 2.

There are different causes for coffin joint flexion. The flexion may be pre-existing, such as in clubfoot involving the deep digital flexor tendon. However, the flexor muscles may be cramped due to pain in the hoof or deliberately raising the heel in therapy, causing flexion.

These possibilities are easily diagnosed on X-ray and patient examination. After determining the nature and cause of the rotation, the second step is to develop a treatment strategy as to how to counteract the problem. The situation before laminitis developed should be considered – whether the flexion or extension existed beforehand or the situation was provoked by how we treated the hoof.

[1] All X-ray images courtesy of Sabine Wallner, veterinary surgeon.

2. Coronary corium and coronet

The papillae on the coronary corium normally point downwards, but the sinking coffin bone compresses them into the horizontal position. This is almost always the case in acute founder. This is not necessarily the case in latent laminitis, and the papillae on the coronary corium remain roughly in their normal orientation.

Coronary horn produced on the horizontally oriented papillae on the coronary corium will lead to the typical fold found in laminitis. The horn tubules above these new horn folds are closer to the original orientation.

Unfortunately, I cannot show you a picture with acute horizontally oriented coronary corium papillae as we did not have any hoof available for section at this stage. A number of dissertations have images that illustrate this well, though.

The horn fold structure shows whether the likely cause of deformation lies in a sinking coffin bone or toe wall rotation.

Forces on the hoof capsule may actually restore the coronary corium papillae to their original orientation. This orientation of the papillae may also arise when the toe wall deforms forward and the lever forces at that point counteract this process.

Forces transferred through the side walls make this possible. These run diagonally across the hoof, so the tensile and compressive forces on the side walls act on the respective opposite coronet and contribute to the coronet’s shape. However, cracks or missing wall sections may interrupt this force transfer.

Taking these forces into account and applying them during hoof treatment may improve the alignment of the corium papillae on the toe wall in relation to the ground.

The more stable the hoof wall, the easier it is to arrange the forces acting on the hoof.

The frequently practised removal of the toe wall may eliminate leverage forces on the overlying coronet and suspensory apparatus, but the stabilising force is also lost causing the side walls to tend to drift apart.

The side walls cannot transfer forces to the coronet in the toe area without the toe wall. Collagen fibres connect the coronary corium, lamellar corium and sole corium to the coffin bone. The hoof wall’s shape and orientation affect the tension on these collagen fibres. Laminitis and sunk coffin wall, and also wall rotation or concave and convex deformation or shaping on the hoof walls causes strain on the fibres, even ending in torn fibres depending on disease severity.

Figure 11 to 13: Coronet with varying toe wall alignment

To be sure, tension changes to the fibres on the coronet can also occur in a healthy hoof. We should always consider their impact on the coronet in shaping the hoof wall.

Position changes on the hoof capsule and limb are mainly intended with consequences for the joints, tendons and ligaments in mind, ignoring the effects of sudden change in fibre position on the corium. In my experience, a minor change is enough to provoke founder again in a hoof affected by laminitis.

3. Hoof wall and lamellar corium

Broadening is the most well-known alteration to the suspensory apparatus of the hoof. The cornified lamellae on the hoof wall separate from the lamellar corium in the first stage, after which cornified scar tissue closes the gap again in the second stage. The X-ray image will show the front of the coffin bone no longer running parallel to the hoof wall.

Potential separation in the fibrous layer of the lamellar corium is a less well-known consequence. Wall rotation will also show up on X-ray in this case.

The trimmers amongst you will know the phenomenon that the laminar layer is not widened as the rotation on the X-ray image would suggest. One of the possible causes may be broadening in the fibrous layer. That could mean that the gap between the hoof wall and coffin bone can never quite close up again.

The coronary horn not running parallel to the coffin bone inevitably means that the lamellar corium has changed in its anatomy. There are several possibilities for this. The following figures show two examples – one is a curved toe wall and straight coffin bone, and the other is a curved coffin bone and a more stretched toe wall.

Trimming may partly explain the causes of these variations in anatomy. As an example, I was told that the horse with the hoof specimen shown in Figure 16 had already had the hoof trimmed in this oblique direction over a longer period. I do not have any information on the horse from Figure 17, but if you look closely you can see that the hoof wall also tends towards curved shape here. The long cover of the wall obliquely oriented towards the ground causes the stretched appearance of the wall. This combination leads to broadening in the corium on the coffin bone edge.

Maybe we should stop seeing stretched hoof walls as the only ideal form and forcing hooves into this ideal.

These examples show once again how important it is to consult not only the X-rays but also to match the history of the hoof with the imaging methods for a reliable diagnosis. We need to gain an accurate idea of how visible changes affect corium anatomy, as this is the only way of deciding on therapeutic measures to match the individual patient.

I have several specimens with a steeper or curved hoof wall in the lower part of the hoof. All these specimens show a broadened region in the fibres on the coffin bone to the laminar part of the lamellar corium. This warrants the following questions: How far will this hoof shape affect blood flow to the lamellar corium and through the entire hoof? How much will this hoof condition contribute to hoof destabilisation? I have not yet found any answers to these questions.

4. Sole corium and edge

Changes to the sole edge take place whenever the sole corium is exposed to non-physiological pressure and tension conditions, especially on the reticular dermis as is always to be expected in laminitis with sunk and/or rotated coffin bone. Excessive pressure on the corium may even arise with a thin stratum corneum at the sole edge where the hoof has no cover. The corium changes structure and wraps around the coffin bone edge. The reticular dermis is thinner, the papillae on the sole corium are oblique to the toe. The terminal papillae are higher on the dermal lamellae on the lamellar corium. Lipping will form, albeit inconspicuously at the beginning.

5. Side walls of the hoof

The side walls receive too little attention in classical laminitis treatment in my opinion. These compress upwards when the load is taken completely off the toe wall. This typical curve at the coronet can be observed in many hooves with laminitis (see Figure 5, Figure 18, and also Figures 23, 24 and 26, 27).

Laminitis also affects the suspensory apparatus on the side wall – first due to the laminitis itself, and second due to overloading as the toe wall no longer supports any load. Remember that the side walls have to take around one and a half times the load when the toe wall curve is not supporting any load, such as after toe wall resection.

This means that lipping may also very well arise on the sides of the coffin bone, sometimes even more so than at the toe wall.

Coffin bone edge in the specimens shown in Figures 3 to 5

6. Chronic laminitis

Failure to stop and possibly reverse the changes set in motion by laminitis will result in the changes progressing; the laminitis hoof can no longer be restored to the condition of a normal hoof.

Changes to the corona, sole edge, lamellar corium and coffin bone are linked. This means that any change to one of these structures will always involve changes to the other structures.

These changes always look similar from the outside, but there are still major differences on the inside.

In my opinion, the focus in treating laminitis is placed too narrowly on treating the levering toe wall and removing the cornified wedge of scar tissue. Removing too much of the toe wall wastes the opportunity of creating a positive impact on the corona from the side walls. However, the horn begins to grow at the corona; a healthier hoof will need this in the future. In addition, the side walls are too heavily burdened with the above effects.

We often expect too much from chronic laminitis. Some of the changes such as lipping cannot be reversed. I have never seen the changes to the reticular dermis on the sole or broadened reticular dermis on the wall and coronary corium reversed. In my opinion, it makes more sense to “restore” the problem sites on the hoof and become accustomed to the idea that an ideal hoof will remain out of reach.

7. Practical application of these findings

Najade, an eighteen-year-old Aegidienberger mare with a history of laminitis going back years: I have assessed the X-ray such that although there is slight rotation in the coffin joint, this is not as extensive as the distorted fetlock line would suggest – the navicular bone is only slightly pushed upwards.

Najade had severe cramp in the flexor muscles resulting in heavy tension on the deep flexor tendon. I did not see any potential for correction in the coffin joint due to hoof cartilage ossification.

The navicular bone connects to the cartilage, and I did not expect this connection to be flexible any more. So I did not consider changing the position by applying packing material or lowering the heels, even for a short period. Apart from that, even the smallest change in position would certainly have had a negative effect on the fibrous connections from the corium to the coffin bone, which were already strained.

The hoof wall was already rotated far forward from the corona. The fold in the horn also showed that restoring the forward-facing papillae on the coronary corium should at least be possible. This would require a toe wall which, although minimised at the lever, would transfer force to affect the coronary corium via the heels and heel walls. The perioplic horn should help realign the coronary papillae, and was therefore very well-treated.

The fibres attaching the coronet and its subcutis to the coffin bone were stretched. A hoof wall rasped in the lower third and rounded to a “bull nose” or a strongly rounded hoof wall could have led to further stretching in the fibres. We needed to avoid that so as not to waste what might have been the last chance to restore the corona to more favourable alignment.

The suspensory apparatus shown was greatly broadened, but not as much as it appeared on the X-ray; the laminae on the hoof were not wide enough. This was also due to the sole horn being pushed horizontally over the laminae, thus partly covering them. I also assumed that the fibres attaching the laminar corium to the coffin bone were stretched at least in the lower area.

The broadening in the suspensory apparatus may be reduced again if the hoof wall is steepened starting at the corona, but I am unaware of successfully applying this on a broadened fibrous layer. My expectations for the future included a more functional hoof wall with narrower laminae, but not an entirely parallel hoof wall.

I saw another problem in the coffin bone tip, which had already undergone heavy change involving corium displacement. The X-ray and the hoof itself showed horizontally shaped sole horn towards the front. The usually thick reticular dermis on the edge of the hoof was virtually non-existent, as it is in many cases after years of laminitis. The papillary corium on the sole had wrapped itself around the changing coffin bone tip. In my opinion, these are changes that can no longer be reversed. My aim here was to prevent further deterioration in the future. In my opinion, this would involve reducing pressure from the ground to the edge of the sole near the hoof toe, regardless of whether the sole was thick or thin. The horizontally oriented sole tubules tensed the corium with pressure from the ground, so this hoof needed a certain distance from the ground using the less heavily affected side walls. The length of the sole horn tubules needed to be kept as short as possible. This also prevented the sole from covering the laminae and made it easier for the cornified scar tissue on the laminae to be pushed downwards unhindered. The laminae would otherwise be locked in place and squeezed up between the coffin bone and hoof wall, which would have caused further broadening in the suspensory apparatus as it made space for itself.

The coffin bone was supported at the sides and the thin soles were protected with light packing under the coffin bone tip as long as the hooves still ached. The separation extended from the toe deep into the side walls, so the heels were the only part of the hoof that were able to take the load without causing pain, so preventing the usual position in laminitis with the front hooves extended was out of the question. The necrotic processes that arise in the laminae and often in the soles needed to be treated as a matter of urgency.

Treatment on Najade began in March 2016, but the founder lasted until May 2016. Hoof ulcers arose on the toe and proceeded across the front of the sole in June 2016. As of August 2016, Najade walked very well even without hoof protection until I trimmed them in October 2016, which led to a significant deterioration in her gait. I had become too impatient and wanted to achieve too much too soon. November 2016 saw a movement disorder clearly originating in the hindquarters. The front hooves were no longer sensitive at this point. The horse owner’s research unearthed the cause of the movement disorder in the hindquarters – tannins in the sainfoin feed that Najade had been receiving to support her metabolism. Najade was finally able to walk on soft surfaces without hoof protection again from January 2017.

The hooves’ appearance deteriorated markedly with increasing zest for movement, but used hooves often look less beautiful than unused hooves. I try not to let that bother me, and I am glad that the horse is walking well.

Najade’s hooves will probably never completely recover, but they will now be good enough for a retired mare with a light workload. She can even walk without hoof protection and a lightweight person riding her around the paddock, which would have been impossible even in the last few years before the severe founder.